From Stars to Soils: An Astronomer’s Journey into Molecular Biology

When you think of the field of astronomy, you’re probably not thinking of things like microbes that live in the dirt under our feet. So…how does an astronomy major end up in a molecular biology Ph.D. program?

My name is Adriana Gomez-Buckley, and I’m a graduate student at the University of Arizona in the Carini Lab. As an undergraduate at the University of Washington, I majored in astronomy and physics, but now I’m a graduate student in the Molecular and Cellular Biology program. This isn’t as disconnected as it initially sounds. While a lot of astronomy involves things like planetary physics, star life cycles, and trying to peer into the furthest reaches of space, there is also astrobiology - an interdisciplinary field which, broadly, studies life on other worlds. I dove into an astrobiology research project with Dr. Michael Wong in my final years of undergrad, which sparked my interest in using life in environments on Earth as analogues for similar environments on other worlds. My undergraduate research took a model of bacteria and viruses in the Arctic Sea ice and applied it to Europa, the ice-covered ocean moon of Jupiter. We found that life could exist on the underside of the ice cover, potentially in the form of biofilms, similar to what we see on Earth in icy waters.

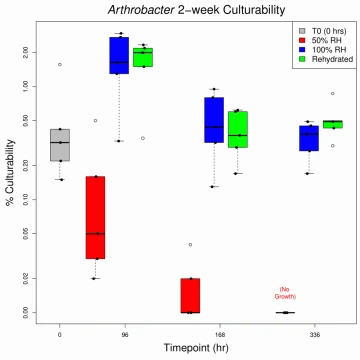

I loved using hands-on science on the ground to inform our understanding of the larger universe. This was what led me to my current work with Dr. Paul Carini, where I’m taking a closer look at how life can survive without water. You might think that cells in desert soils would die during the driest times of the year, but most actually enter a dormant state, waiting for water to rehydrate and revive them. I want to understand how exactly they survive, and how RNA - the blueprint for all living things - is involved in this. We think that it stays “frozen”, in a sense, so that microbes can use it when they wake back up, but this is still unclear. And the waking up process is another unstudied area I want to delve into. Just like someone dumping a bucket of cold water on you to wake you up is more startling than a gentle shake on the shoulder, dunking dried out cells in liquid water is worse for their recovery than a slow rehydration with water vapor.

With further research, we could unlock some of the mysteries surrounding how cells survive while dried out and dormant. Not only would this help with a lot of things on Earth - say, drying out food for preservation - it would also be beneficial to astrobiology. Understanding how microbes in the desert soil survive could tell us more about how life could exist on other dry worlds, like Mars.

So, to answer my question - how does an astronomer end up in a biology Ph.D. program? Sometimes you have to go small to go big, and look at the smallest organisms to understand more about our universe.